As an artist, scuba diver, and ocean advocate, Jacquelyn Dale (JD) Whitman creates art that educates the public on our oceans and inspires participation in global conservation efforts.

Whitman is an MFA candidate in art at the University of Iowa, with emphases in sculpture and photography. In her upcoming thesis project, Whitman will combine art with marine ecology to uniquely inform viewers on a decline in marine biodiversity due to human threats. To achieve this, she will share Ireland’s Blaschka Invertebrate Models—glass replicas of marine invertebrate species from our 19th-century oceans—with the public through an interactive, sculptural installation made from recycled plastic and animated video projections of these models.

Invertebrates are animals that do not have a spinal column or backbone such as insects, crabs, and giant squid. They make up an estimated 97 percent of all species on the planet, ensure habitat quality, serve as the foundation for most food chains, and sustain both marine and terrestrial ecosystems. However, marine invertebrates are declining in rapid numbers due to human threats like habitat destruction, overfishing, invasive species, pollution, and climate change.

The United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) predicts that without significant, global changes, more than half of the world’s marine species will stand on the brink of extinction by 2100.

“This installation will positively educate viewers on the global decline in marine biodiversity due to the threat of plastic pollution,” says Whitman, a native of Philadelphia, Pa. “Almost every single food chain and ecosystem depends on invertebrates. If we eliminate the invertebrates, it is doubtful that we as a species will survive. If we remove just one of the human threats—if we work to resolve the plastic pollution crisis—that could help to reverse this potentially catastrophic, global decline.”

Whitman’s thesis exhibit was publicly displayed March 18-24 at the Drewelowe Gallery in the Visual Arts Building. On Saturday, March 24 from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m., families brought their children to explore the exhibition space, learn about marine invertebrates and recycling, and participate in making collaborative artwork that will become a part of the exhibit.

Blaschka Invertebrate Models

Created and shared worldwide during the Victorian era by Leopold and Rudolph Blaschka, the Blaschka Invertebrate Models serve as a precise marker of a decline in marine biodiversity since the 19th century.

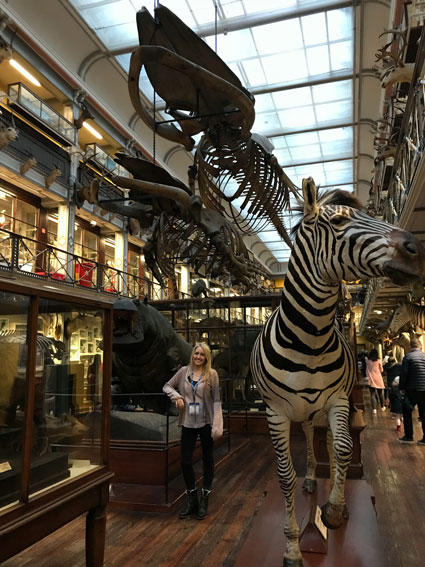

The National Museum of Ireland-Natural History in Dublin, Ireland houses one of the largest collections of Blaschka Invertebrate Models in the world. However, the majority of their 556 items were not documented or catalogued until last summer.

Whitman spent the summer at the museum developing standardized methods of photographing each invertebrate to initiate the digital preservation of the collection. Due to museum regulations and object fragility, the only current way to publicly share these models is through photography.

The UI graduate student photographed 120 models during her two-month trip, which was funded and supported by the School of Art and Art History and the Graduate College. Whitman will return to the National Museum of Ireland-Natural History this August to complete her work on the project.

“One of the reason the Blaschkas are so important is because some of them are the only remaining examples of marine invertebrates that have gone extinct,” Whitman says.

Nigel Monaghan, keeper of the Natural History division at the National Museum of Ireland, is impressed with Whitman’s fascination and passion about working with the Blaschka collection.

“Jacquelyn’s infectious enthusiasm is why she got to do this project in the first place,” Monaghan says. “She convinced us as a museum to put our trust in her and devote time and facilities to a project that has more than repaid our input.”

“As a scientist, I see the practical results of the project, but I also learn about its aesthetics from her as an artist. It gives me great satisfaction in seeing our collections exposed to wider audiences.”

Monaghan says the museum receives 330,000 visitors annually.

“People are endlessly fascinated by the tiny marine creatures modelled by the Blaschkas,” he adds.

Combating ecophobia

While the Blaschka installation is her thesis project, during her time as a graduate student at UI, Whitman has constructed a series of sculptural installations that utilized art to educate people on complex scientific concepts and human threats to marine ecosystems.

Whitman combines her photographs taken while scuba diving with photographs of her own sculptures to produce 2D animations that are then projected onto large-scale sculptural objects made entirely from recycled plastic. As people walk through her sculptural installations, they feel as if they are actually underwater due to the sculpture’s dynamic command of physical space, the larger-than-life projections of marine visuals illuminating that space, and the immersive application of audio narratives.

“I can look at her work and see her message. She is very committed to getting her message across,” says Isabel Barbuzza, UI associate professor of sculpture and Whitman’s advisor. “At the same time, I see an incredible amount of research and an incredible amount of thought that goes into how she makes the installation. When you look at her art, you let the art take over.”

Her installations serve to combat ecophobia—a negative response or automatic desensitization to visual images of environmental disasters. Whitman says ecophobia is partially responsible for the failure of current environmental education efforts and declining ecoliteracy rates in the United States.

Whitman began investigating ecophobia in 2014 as a student at the Burren College of Art in Ballyvaughan, Ireland. She addressed the issues of bycatch and entanglement in one of her installations. Bycatch occurs when non-targeted marine species – such as dolphins, sea turtles, and sea birds – are incidentally captured or tangled in fishing gear. Entanglement occurs when marine species become ensnared in drifting marine debris. Both issues result in the unnecessary death of critical marine species.

Whitman’s 14-foot high installation featured hand-cut, color-printed paper nets displaying photographs of animals caught in fishing gear. When people first walked into the installation, they only saw incredible colors, hanging sculptures, and an intricate web of ever-changing casted shadows before getting a close-up view of the morbid photographs.

“When trying to inform viewers of large-scale marine threats, how you introduce the information is crucial. If you immediately show people a truthful but grisly image of what’s happening, they’ll be upset by it, become emotionally closed off, and be unable or unwilling to learn about what they are seeing,” Whitman says. “I’m trying to circumvent ecophobia by placing people in a positive, immersive environment before slowly introducing a negative truth. An enchanting, all-encompassing visual space allows viewers to digest positive information and establish a sense of empathy towards certain subject matter before gently being introduced to the negative problem affecting it.

“As a witness to a global decline in marine health, I am driven to produce art that effectively educates the public on human threats to marine ecosystems and glorifies the wonder of our once eternal oceans.”